I have broken my silence because I am seriously concerned. The National Statistician's Review of Crime Statistics in England and Wales was published yesterday. This is what my last post but one referred to. I got the person of the National Statistician wrong. It is now Jil Matheson pictured above with Prime minister David Cameron and on her own.

Unsurprising she has recommended that the Office of National Statistics should take responsibility for crime statistics away from the Home Office. This recommendation 5. Recommendation 1 is:

"The body responsible for the publication of crime statistics should seek to improve the presentation of the statistics to give users and the public a clearer understanding of the overall picture of crime, by providing the major and other sources of crime statistics together with additional contextual information."

This will only happen if the statisticians understand the raw data they present. Figure 1 shown above of the report and the explanatory paragraph, clearly shows they do not understand the scope of police incidents. At best the paragraph and figure present a confusing, unclear explanation. In fact it is totally wrong, worryingly wrong, because whoever wrote paragraph and compiled the figure does not have the first clue about the reporting mechanisms resulting in police recorded crime and the contents of the incident database.

The incident database has details of less than 50% of notifiable offences that end up being counted as police recorded crime but contains hundreds of thousands of incidents that come within recorded crime categories that are not counted as police recorded crime. Additionally not all of the 4.3 million notifiable offences are mapped because either they have no mappable location or the fall outside the categorises that are mapped.

Search This Blog

Wednesday, 8 June 2011

Monday, 14 March 2011

What is Geographic Information Science (GISc)?

I am aware that I have not posted for sometime. This is because I have been trying to get my thoughts together to start writing my PhD thesis. I thought I would post part of my introductory section discussing Science and Geographic Information Science (GISc). Without GISc there would be no crime maps so it is quite important. Everything I know about the subject and a lot more is contained in the excellent bestselling book in the world on the subject, that has recently been published in its 3rd edition - "Geographic Information Systems and Science" whose lead author just happens to be one of my supervisors - Professor Paul Longley.

What I am trying to do is explain why GISc is undoubtaby a science (something I needed to be convinced about when I first approached the subject) and to start laying the ground work to justify creating and comparing classifications between areas using crime and policing data.

Science

This section discusses the scientific context of the research. The discussion adopts a simplified approach, guided by others who have studied and written about the nature of science, its definitions and its academic divisions. These processes of definition, simplification, clustering and classification, often in an inexact and overlapping way, are of course central to the scientific method and central to the research carried out in this thesis.

The word ‘science’ is derived from the Latin via Old French and Middle English to denote ‘knowledge’ (Oxford online Dictionary). The purpose of all science is to transform raw data by analysis and/or experimentation into knowledge (Oxford online Dictionary, Longley et al 2010). Knowledge in this sense is an understanding of the system that is being studied so that it can be described by relationships, laws or theories that model its key dynamics. This is a process that goes further than describing a system by providing an insight into how it works. Part and parcel of understanding a system is to be able to identify uncertainties and where possible quantify them; the statistical use of confidence levels of results is an example of this. This quantification of variables and relationships allows research to be reviewed by peers with a view to validation and the generation of new knowledge through further scientific research.

Geographic Information Science (GISc)

The over-arching methodology used by this thesis is Geographic Information Science (GISc). Geography is defined by the (Oxford online Dictionary) as;

“the study of the physical features of the earth and its atmosphere, and of human activity as it affects and is affected by these, including the distribution of populations and resources and political and economic activities.”

The use of the word ‘Information’ refers to the organised collection of data, for instance in a database. GISc relies on Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for the storage of geographic data and organising it so that it can be used for scientific purposes. The data in GIS come from a myriad of different sources, some of which are specific to the creation of mapping the surface of the earth such as satellite imagery and others that are by-products of other data gathering activities such as census data and land-ownership. The data from the disparate data sources are linked by the fact that each row of data in every data set in the system is geo-referenced. This allows the joining of the different data by location or the keeping the data sets separate by layering the data by location or a combination of both. This leads to mentioning the special nature of spatial data that is based on the Tobler’s first law of geography;

“Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” (Tobler 1970).

Tobler’s law refers to spatial autocorrelation which affects the independence of variables which are analysed spatially. This spatial autocorrelation is two dimensional (unlike temporal autocorrelation which is one dimensional) because it radiates out from a fixed point. Both these facts necessitate the use of spatial statistics if the spatial nature of variables is being assessed. The complex nature of the application of Toblar’s Law to crime and policing data is discussed further in this thesis.

The creation of maps is a scientific process, representing the real world is a process of scale selection, data choice and emphasis based on purpose, generalisation and geovisualistion. These methods of representation are by their nature incomplete and imperfect as the only way to perfectly represent the real world is using a 1:1 scale which is pointless and totally impractical. This means that irregular lines on maps, such as coastlines and roads are simplified by excluding the smaller twists and turns; polygon zones are created to show features that are pertinent to the purpose of the map that generalise or amalgamate entities being represented. This can either be completely objective based on measurement and statistical criteria or purely subjective based on the eye of the mapmaker; often it is a combination, this where science meets art. Maps are designed to be intuitive (once the spatial language is understood) by duplicating how human-beings perceive and make sense of the real world both visually and intellectually. Our perception of things goes from the general to the more and more specific as the resolution increases; in a geographical sense, without the aid of maps, this involves travel, for instance moving from seeing a wood in the distance to entering the wood and only being able to see the trees. This raises the question, “Is it better to see the wood or the trees?” The answer is of course “It depends on your purpose.” The conclusion is that, in line with the saying “You cannot see the wood for the trees”, in many circumstances the general can be more important and informative than the specific.

Imperfect clustering and classification are fundamental to GISc. They can be applied to label areas on a map as forests even though there are areas within them of agricultural land or showing the residents of an area as “small town seniors” even though youth offenders are known to live there. The importance of this methodology to this thesis is that it allows hypotheses of relationships between different layers at the same locations to be proposed and comparisons between different locations to be investigated on a single or multi-layer basis. To continue with the tree example, it would be logical to have a polygon denoting timber production on a layer to spatially coincide with a polygon on a separate layer denoting forest but not necessarily all forest polygons spatially coinciding with timber production: If a polygon denoting timber production is nowhere near a forest polygon, this is worth further investigation and explanation.

GISc is a pure science because it is used to empirically measure and represent geographic characteristics and attempts to understand how they interact with each other. It is also an applied science because much of this knowledge is put to practical use, for example Internet crime maps for the public.

What I am trying to do is explain why GISc is undoubtaby a science (something I needed to be convinced about when I first approached the subject) and to start laying the ground work to justify creating and comparing classifications between areas using crime and policing data.

Science

This section discusses the scientific context of the research. The discussion adopts a simplified approach, guided by others who have studied and written about the nature of science, its definitions and its academic divisions. These processes of definition, simplification, clustering and classification, often in an inexact and overlapping way, are of course central to the scientific method and central to the research carried out in this thesis.

The word ‘science’ is derived from the Latin via Old French and Middle English to denote ‘knowledge’ (Oxford online Dictionary). The purpose of all science is to transform raw data by analysis and/or experimentation into knowledge (Oxford online Dictionary, Longley et al 2010). Knowledge in this sense is an understanding of the system that is being studied so that it can be described by relationships, laws or theories that model its key dynamics. This is a process that goes further than describing a system by providing an insight into how it works. Part and parcel of understanding a system is to be able to identify uncertainties and where possible quantify them; the statistical use of confidence levels of results is an example of this. This quantification of variables and relationships allows research to be reviewed by peers with a view to validation and the generation of new knowledge through further scientific research.

Geographic Information Science (GISc)

The over-arching methodology used by this thesis is Geographic Information Science (GISc). Geography is defined by the (Oxford online Dictionary) as;

“the study of the physical features of the earth and its atmosphere, and of human activity as it affects and is affected by these, including the distribution of populations and resources and political and economic activities.”

The use of the word ‘Information’ refers to the organised collection of data, for instance in a database. GISc relies on Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for the storage of geographic data and organising it so that it can be used for scientific purposes. The data in GIS come from a myriad of different sources, some of which are specific to the creation of mapping the surface of the earth such as satellite imagery and others that are by-products of other data gathering activities such as census data and land-ownership. The data from the disparate data sources are linked by the fact that each row of data in every data set in the system is geo-referenced. This allows the joining of the different data by location or the keeping the data sets separate by layering the data by location or a combination of both. This leads to mentioning the special nature of spatial data that is based on the Tobler’s first law of geography;

“Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things” (Tobler 1970).

Tobler’s law refers to spatial autocorrelation which affects the independence of variables which are analysed spatially. This spatial autocorrelation is two dimensional (unlike temporal autocorrelation which is one dimensional) because it radiates out from a fixed point. Both these facts necessitate the use of spatial statistics if the spatial nature of variables is being assessed. The complex nature of the application of Toblar’s Law to crime and policing data is discussed further in this thesis.

The creation of maps is a scientific process, representing the real world is a process of scale selection, data choice and emphasis based on purpose, generalisation and geovisualistion. These methods of representation are by their nature incomplete and imperfect as the only way to perfectly represent the real world is using a 1:1 scale which is pointless and totally impractical. This means that irregular lines on maps, such as coastlines and roads are simplified by excluding the smaller twists and turns; polygon zones are created to show features that are pertinent to the purpose of the map that generalise or amalgamate entities being represented. This can either be completely objective based on measurement and statistical criteria or purely subjective based on the eye of the mapmaker; often it is a combination, this where science meets art. Maps are designed to be intuitive (once the spatial language is understood) by duplicating how human-beings perceive and make sense of the real world both visually and intellectually. Our perception of things goes from the general to the more and more specific as the resolution increases; in a geographical sense, without the aid of maps, this involves travel, for instance moving from seeing a wood in the distance to entering the wood and only being able to see the trees. This raises the question, “Is it better to see the wood or the trees?” The answer is of course “It depends on your purpose.” The conclusion is that, in line with the saying “You cannot see the wood for the trees”, in many circumstances the general can be more important and informative than the specific.

Imperfect clustering and classification are fundamental to GISc. They can be applied to label areas on a map as forests even though there are areas within them of agricultural land or showing the residents of an area as “small town seniors” even though youth offenders are known to live there. The importance of this methodology to this thesis is that it allows hypotheses of relationships between different layers at the same locations to be proposed and comparisons between different locations to be investigated on a single or multi-layer basis. To continue with the tree example, it would be logical to have a polygon denoting timber production on a layer to spatially coincide with a polygon on a separate layer denoting forest but not necessarily all forest polygons spatially coinciding with timber production: If a polygon denoting timber production is nowhere near a forest polygon, this is worth further investigation and explanation.

GISc is a pure science because it is used to empirically measure and represent geographic characteristics and attempts to understand how they interact with each other. It is also an applied science because much of this knowledge is put to practical use, for example Internet crime maps for the public.

Saturday, 19 February 2011

Crime Statistics, are the Statisticians to blame for lack of confidence?

Sir Michael Scholar, the UK's National Statistician, pictured above, has been asked by the Home Secretary to carry out a review of crime statistics with the purpose of increasing public confidence in them. He has published a questionaire that can be found here that anyone can complete and submit. Below are my thoughts. I probably have not started off very well by putting some of the blame for low confidence in the crime statistics on the statisticians themselves, but I try to tell it as I see it. Having heard Sir Michael speak at the Royal Statistical Society I am sure he and his staff will be receptive to my views.

It should be the responsibility of a body independent of government but reports to the Home Office in a similar way that the Bank of England is independent of the Treasury but reports to the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

It would a mistake for it to be given to the UK Statistics Authority as I think that one of the major problems that needs to addressed is the fact that it is obvious that the statisticians do not understand the data fully, given its legal and procedural subtleties and have difficulty in producing reports that the policy makers or the public properly understand.

It would a mistake for it to be given to the UK Statistics Authority as I think that one of the major problems that needs to addressed is the fact that it is obvious that the statisticians do not understand the data fully, given its legal and procedural subtleties and have difficulty in producing reports that the policy makers or the public properly understand.

There is far more to crime statistics than just statistics, a major part of it is understanding crime and policing; which are the domains of criminology and police science. With the increasing use of maps to communicate the statistics to the public the discipline of Geographic Information Science is becoming more and more important.

Q2: Is there also a case for transferring responsibility for the management and/or compilation of data collected from the British Crime Survey and the police ? If so, where?

The National Audit Office should be seriously considered for police recorded crime. Even though the data is not financial per se, the skill sets of auditors are very compatible. One of the main challenges to the accuracy and integrity of police recorded crime statistics is that they are used as primary measures of police performance. The procedures for managing and collecting crime statistics to ensure uniformity within and between police forces needs to be overseen by people who have the forensic skills to identify deliberate under recording. As crime reduction and clear-up rates are directly related to individual police officers promotion prospects and pay the auditors should also have sanctions that they can enforce on individuals.

The British Crime Survey (BCS) should be totally independent of the police recorded crime statistics and pressure from the government. It has been a mistake to have one official publication trying to link police recorded crime with the BCS because it makes it look that the two sets of data can be compared directly. In most cases there are reasons why they cannot (due to business and youth crimes not being included for instance) the only notable exception is residential burglaries (but the fact that the BCS uses a rolling 12 month period and the police statistics use a fixed 12 month period affects this and the others crimes). As far more data is collected by the BCS than are published in the resulting dual publication it has the feel that the BCS data is being used to put a political spin on the police recorded crime data. This is at the hub of the need for independence. As important is the long term funding of the BCS so there is not a pressure to please the funding master/mistress to gain continued support.

The linking of different crime data sets should be done independently by academics and those putting them to practical use.

Another solution is to make the two data sets directly comparable which is preferable – see the 4th paragraph of the answer to Q5.

Q3: Currently, the Home Secretary determines what is recorded by the police as a crime and approves the Home Office Counting Rules for crime and statutory data requirements from the police. Should this continue or would public trust in the statistics be enhanced if this responsibility moved elsewhere? If so, where and why?

The Home Office should determine police priorities and ensure that bureaucracy is minimised; these are levers for doing this. The agency managing the collection of the police recorded data, my suggestion the National Audit Office, should be required to comment on whether the rules and requirements properly reflect the level and nature crime in the country.

Crimes in crime statistics always have a legal definition and sometimes in addition a descriptive label. For instance in law there is no offence of burglary dwelling, snatch, armed robbery, it is burglary, theft and robbery (with firearms offences). The labelling in the main allows offences against vehicles to be distinguished and with a bit of delving those offences against people; this should be made clearer. Equally important are those crimes that occurred in a private place or a public place. Under the present labelling it is often not possible to make any inferences in this regard. I think this is vital to understanding the crime problem and police performance.

There are ten Home Office (HO) crime types. The one that leads to the most misunderstanding, confusion and distrust is HO crime type 1 – violence against the person. It is not helped by the fact that statistics that are derived from it are referred as ‘violent crime’ by Home Office publications and politicians. The public order offence of violent disorder (that usually includes violence against the person but not necessarily) which is not included in HO crime type1, shows that violent crime in law applies to criminal damage as well as assaults. This aside, robberies, sexual assaults, aggravated burglaries, kidnapping and arson endangering life which are specifically violence against the person offences are not included in HO crime type 1. The inclusion of common assault (section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988) in the sub-type of ’without injury’ is misleading because there almost always is an injury but not of a permanent nature; only assaults without battery should be included in this sub-type.

If the category of violent crime is important to the public and politicians, which I believe it rightly is, then all crimes that are violent should be included in that category with sub-categories as necessary. If this means double counting of certain crimes because they also meet the criteria of another category, this should not be a problem as long as it is properly explained.

Official Crime Statistics have taken advantage of police computerisation of crime records in the collection of data but not in the scope of what data is collected.

Police accountability and crime prevention would be aided by counts of characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, geodemographic group for instance) of victims of crime and suspected offenders broken down by crime types and offences. Advances have been made in providing location data about crimes through the medium of maps on the Internet, the accountability and crime prevention advantage could be further enhanced by the provision of data of when (date, day, hour) offences had been committed and/or discovered.

The dark figure of unreported and unrecorded crimes is very important to assessing police performance and confidence in police. I would argue the best proxy measure of confidence in police and police efficiency is the size of that dark figure which is known to vary from offence to offence. The BCS was originally set-up to shed light on this dark figure but as I have mentioned in my answer to Q2 the lack of direct comparability of the two data sets affects the confidence in the accuracy of the estimates produced. A reliable figure can be produced of unreported and reported BCS crimes but the figure for reported and unreported police recorded crime is less reliable. This makes the important figure of those crimes reported to the police but not recorded by the police also unreliable.

The solution to this is not to change the methodology of the BCS but to extract only those crimes that are covered by BCS from the police crime computers for comparison purposes. This is feasible given the data contained within each police crime record and the modern searching power of computers. If the characteristics of victims was also included then very useful assessments of police engagement with different communities would result and provide a good proxy indicator of the level of confidence different communities have in the police. The accurate assessment of the nature of the dark figure for different offences would provide a good measure of police effectiveness and efficiency. This would balance police recorded crime reduction targets that can be achieved through the public feeling that it is not worthwhile reporting crimes to the police.

The Reassurance Gap that led police to realign resources from response policing to neighbourhood policing arose because the public perceived that the crime problem was getting worse even though the official crime figures were showing year on year improvements. The analysis of this included an assessment that one of the reasons for this was that the official crime figures did not match the experiences of people. Drawing on Incivility Theory from the USA and the newly developed Signal Crime Perspective in the UK it is generally agreed that the observable nature of crime and disorder rather than officially collected crime figures influence people’s perception of crime and therefore their level of fear of crime. The all pervasive low level disorder (antisocial behaviour or incivilities) has as much influence, if not more, than the observation of serious crime on people’s perception. Police recorded crime, because of the way it is collected and legally categorised will never be totally in tune with people’s perceptions. My research includes analysing police incident data to see if the data can be used to produce maps that more closely match people’s observations of crime and disorder. The importance of this is that if policy makers and police have a view of the policing problem in a neighbourhood that is not matched by the communities living and frequenting there then there will be a mismatch of priorities and expectations. Research has shown that trust is based on good engagement and communication, crime statistics and maps based on them can either alienate or engage. Police incident data is being used to map anti-social behaviour but it should be used much more widely to reflect the nature and levels of violent crime. Police incident data has the added value of having good temporal attributes and shows details of the police response and priorities, and also the priorities and engagement of the public.

The most important consideration for trustworthy crime statistics is that they are understood. The Home Office Counting rules, legal definitions, Home Office Crime Types, especially in relationship to violent crime are all barriers to proper understanding of police recorded crime. The intricacies of methodology and statistical techniques are barriers to properly understanding, evaluating and therefore trusting the BCS statistics.

The police incident data set is in everyday language, it reflects what people observe and it is easy to explain the origins and validity of the data. It cannot replace the police recorded crime statistics or the BCS but it enables the public to know and understand what the police in their local area are dealing with on a day to day basis. My evaluation of police incident data shows that police recorded crime probably accounts for fewer than 50% of their workload of crime and disorder related. This means that crime statistics would be considerably enhanced as a performance measure if police incident data were included.

The National Audit Office should be seriously considered for police recorded crime. Even though the data is not financial per se, the skill sets of auditors are very compatible. One of the main challenges to the accuracy and integrity of police recorded crime statistics is that they are used as primary measures of police performance. The procedures for managing and collecting crime statistics to ensure uniformity within and between police forces needs to be overseen by people who have the forensic skills to identify deliberate under recording. As crime reduction and clear-up rates are directly related to individual police officers promotion prospects and pay the auditors should also have sanctions that they can enforce on individuals.

The British Crime Survey (BCS) should be totally independent of the police recorded crime statistics and pressure from the government. It has been a mistake to have one official publication trying to link police recorded crime with the BCS because it makes it look that the two sets of data can be compared directly. In most cases there are reasons why they cannot (due to business and youth crimes not being included for instance) the only notable exception is residential burglaries (but the fact that the BCS uses a rolling 12 month period and the police statistics use a fixed 12 month period affects this and the others crimes). As far more data is collected by the BCS than are published in the resulting dual publication it has the feel that the BCS data is being used to put a political spin on the police recorded crime data. This is at the hub of the need for independence. As important is the long term funding of the BCS so there is not a pressure to please the funding master/mistress to gain continued support.

The linking of different crime data sets should be done independently by academics and those putting them to practical use.

Another solution is to make the two data sets directly comparable which is preferable – see the 4th paragraph of the answer to Q5.

Q3: Currently, the Home Secretary determines what is recorded by the police as a crime and approves the Home Office Counting Rules for crime and statutory data requirements from the police. Should this continue or would public trust in the statistics be enhanced if this responsibility moved elsewhere? If so, where and why?

The Home Office should determine police priorities and ensure that bureaucracy is minimised; these are levers for doing this. The agency managing the collection of the police recorded data, my suggestion the National Audit Office, should be required to comment on whether the rules and requirements properly reflect the level and nature crime in the country.

Q4: The Terms of Reference for the review asks for consideration of the current definitions of crime. Do you have any comments?

There are ten Home Office (HO) crime types. The one that leads to the most misunderstanding, confusion and distrust is HO crime type 1 – violence against the person. It is not helped by the fact that statistics that are derived from it are referred as ‘violent crime’ by Home Office publications and politicians. The public order offence of violent disorder (that usually includes violence against the person but not necessarily) which is not included in HO crime type1, shows that violent crime in law applies to criminal damage as well as assaults. This aside, robberies, sexual assaults, aggravated burglaries, kidnapping and arson endangering life which are specifically violence against the person offences are not included in HO crime type 1. The inclusion of common assault (section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988) in the sub-type of ’without injury’ is misleading because there almost always is an injury but not of a permanent nature; only assaults without battery should be included in this sub-type.

If the category of violent crime is important to the public and politicians, which I believe it rightly is, then all crimes that are violent should be included in that category with sub-categories as necessary. If this means double counting of certain crimes because they also meet the criteria of another category, this should not be a problem as long as it is properly explained.

Q5: It has been said that the crime statistics provide a partial picture. What, if any, are the main gaps in Home Office crime statistics that you feel should be addressed as a priority?

Official Crime Statistics have taken advantage of police computerisation of crime records in the collection of data but not in the scope of what data is collected.

Police accountability and crime prevention would be aided by counts of characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, geodemographic group for instance) of victims of crime and suspected offenders broken down by crime types and offences. Advances have been made in providing location data about crimes through the medium of maps on the Internet, the accountability and crime prevention advantage could be further enhanced by the provision of data of when (date, day, hour) offences had been committed and/or discovered.

The dark figure of unreported and unrecorded crimes is very important to assessing police performance and confidence in police. I would argue the best proxy measure of confidence in police and police efficiency is the size of that dark figure which is known to vary from offence to offence. The BCS was originally set-up to shed light on this dark figure but as I have mentioned in my answer to Q2 the lack of direct comparability of the two data sets affects the confidence in the accuracy of the estimates produced. A reliable figure can be produced of unreported and reported BCS crimes but the figure for reported and unreported police recorded crime is less reliable. This makes the important figure of those crimes reported to the police but not recorded by the police also unreliable.

The solution to this is not to change the methodology of the BCS but to extract only those crimes that are covered by BCS from the police crime computers for comparison purposes. This is feasible given the data contained within each police crime record and the modern searching power of computers. If the characteristics of victims was also included then very useful assessments of police engagement with different communities would result and provide a good proxy indicator of the level of confidence different communities have in the police. The accurate assessment of the nature of the dark figure for different offences would provide a good measure of police effectiveness and efficiency. This would balance police recorded crime reduction targets that can be achieved through the public feeling that it is not worthwhile reporting crimes to the police.

The Reassurance Gap that led police to realign resources from response policing to neighbourhood policing arose because the public perceived that the crime problem was getting worse even though the official crime figures were showing year on year improvements. The analysis of this included an assessment that one of the reasons for this was that the official crime figures did not match the experiences of people. Drawing on Incivility Theory from the USA and the newly developed Signal Crime Perspective in the UK it is generally agreed that the observable nature of crime and disorder rather than officially collected crime figures influence people’s perception of crime and therefore their level of fear of crime. The all pervasive low level disorder (antisocial behaviour or incivilities) has as much influence, if not more, than the observation of serious crime on people’s perception. Police recorded crime, because of the way it is collected and legally categorised will never be totally in tune with people’s perceptions. My research includes analysing police incident data to see if the data can be used to produce maps that more closely match people’s observations of crime and disorder. The importance of this is that if policy makers and police have a view of the policing problem in a neighbourhood that is not matched by the communities living and frequenting there then there will be a mismatch of priorities and expectations. Research has shown that trust is based on good engagement and communication, crime statistics and maps based on them can either alienate or engage. Police incident data is being used to map anti-social behaviour but it should be used much more widely to reflect the nature and levels of violent crime. Police incident data has the added value of having good temporal attributes and shows details of the police response and priorities, and also the priorities and engagement of the public.

Q6: What are the most important considerations for trustworthy crime statistics?

The most important consideration for trustworthy crime statistics is that they are understood. The Home Office Counting rules, legal definitions, Home Office Crime Types, especially in relationship to violent crime are all barriers to proper understanding of police recorded crime. The intricacies of methodology and statistical techniques are barriers to properly understanding, evaluating and therefore trusting the BCS statistics.

The police incident data set is in everyday language, it reflects what people observe and it is easy to explain the origins and validity of the data. It cannot replace the police recorded crime statistics or the BCS but it enables the public to know and understand what the police in their local area are dealing with on a day to day basis. My evaluation of police incident data shows that police recorded crime probably accounts for fewer than 50% of their workload of crime and disorder related. This means that crime statistics would be considerably enhanced as a performance measure if police incident data were included.

Q7: What do you consider to be the main strengths of crime statistics?

The main strength of crime statistics especially when applied to a local level through mapping is that they are extremely popular. This provides an excellent communication and engagement tool that should be used positively and honestly.

Police need to exploit this popularity by including police activity data within their maps to reassure the public and demonstrate their worth to society that is far more than what is revealed in the present crime statistics.

Q8: Do you have any other views you wish to feed into this review?

The spatio-temporal characteristics of offences are extremely important to crime prevention as are the characteristics of victim and offenders for crime prevention and public engagement. This points to an integrated system of maps using police recorded crime, police crime system, police incident management system and BCS as source data. My PhD research involves designing such a system with spatio-temporal clustering and classification at its heart.

Saturday, 12 February 2011

CAD incidents - validation of the k means classification method

This post is really quite interesting if you have following my blog.

I have carried out a simple analysis to test three important aspects of my research;

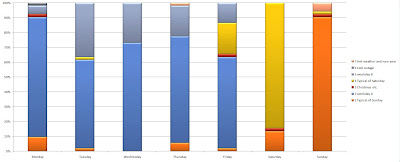

I carried out a k means classification using those four variables with the 365 days of the year as cases (using raw unstandardised data). I asked for seven groups to see if the k means classification could split the days into the right weekdays.

|

| London police violent and acqusitive crime incident in 2009 numbers each day |

I have carried out a simple analysis to test three important aspects of my research;

- How good is the SPSS 17 k means classification method

- Does the Metropolitan Police Service CAD data contain rhythms and cycles that reflect the lives of the people of London and the way it is policed.

- What is the best CAD data to use to detect these rhythms and cycles.

I carried out a k means classification using those four variables with the 365 days of the year as cases (using raw unstandardised data). I asked for seven groups to see if the k means classification could split the days into the right weekdays.

I find the result shown in the graph above quite exciting. I hope you can see why. The classification recognises a clear difference between Saturdays and Sundays and week days. The week days have been subdivided in two groups. I have been through all the dates which appear to have allocated to the wrong group and there is a very good explanation for each. For instance each Monday that was allocated to the typically Sunday group (group1) were Bank Holiday Mondays. Every other "misallocation" had a weather or holiday related explanation.

I have tried the classification with standardised data and additional and fewer variables but these four variables appear to me to produce the best results.

So I now have even more confidence in the k means classification method, I am convinced I using a good set of data and I am sure that analysing the variations in violent and acquisitive crime incidents in the context of the police response is worthwhile.

Thursday, 10 February 2011

Wednesday, 9 February 2011

Comparing Crime and Disorder in London and (greater) Birmingham

What I am doing here is creating a classification by adding West Midlands police neighbourhoods (mostly Wards) to the MPS wards. The first map is of the West Midlands police area - Birmingham is in the centre, Coventry to the east and Wolverhampton to the west. I am grateful to Andy Brumwell, from West Midlands police for providing me with the shapefile.

Monday, 7 February 2011

Google Map crime and disorder .kmz

I have created a .kmz file to be loaded into Google Earth to create the map above. It can be found here. Enjoy.

London Wards December 2010 crime and disorder clustered, classified and mapped

Over the weekend I have been trying to improve on my the map in my last post from a London perspective. London was clustered in a group that I classified as having robbery and burglary problems due to where the cluster centres were for that group. In fact London does have robbery problem according to the figures that were used in the K-means clustering method but the burglary figures showed that London had a burglary problem that was about average. It was the small force of Bedfordshire that was clustered with London that does have a big burglary problem and a also a robbery problem that pushed the centre of the cluster in the direction of burglary.

I have used the same methodology as in the last post to create a classification for London shown above but without dividing numbers by police officers and staff numbers. I have excluded three Wards, Heathrow Villages, St James and West End for two reasons.

Back to the map. In broad terms it shows what I expected. There are a couple of surprises,

I have used the same methodology as in the last post to create a classification for London shown above but without dividing numbers by police officers and staff numbers. I have excluded three Wards, Heathrow Villages, St James and West End for two reasons.

- St James and West End Wards are not shown in the published tables, they are split into eight sub-wards with no information about their locations.

- Heathrow Village is Heathrow Airport that clustered uniquely unsurprisingly, St James and West End always cluster together with a far higher crime rate than any other wards. Removing these gives a better scale to the other Wards.

Back to the map. In broad terms it shows what I expected. There are a couple of surprises,

- the location of the boroughs showing robbery problems, though having checked these do include personal and business robberies; my previous analysis has been exclusively on personal robbery.

- the variation in vehicle crime numbers.

Friday, 4 February 2011

Mapping and Classifying variations Crime and Disorder in forces in England and Wales in December 2010 or variations in recording practices?

In my last post I said that there are fundamental problems with the latest UK crime mapping site. I do not like to be negative about things that people have worked very hard to produce so I created the map above to illustrate the problems and benefits of this initiative.

Firstly how did I create the map?

But what are the data I am classifying and mapping here?

To be honest you I do not know, I could find no documentation to explain. Now I am assuming that the crimes are police recorded crime in Home Office Crime Types but it would not surprise me to find out that there have been problems in ensuring that every force is submitting exactly the same types of crime. The chances of that being uniformly the same is a lot higher than the Anti-Social Behaviour figures, which I am assuming are from the police incident recording database and would not surprise me if they differ significantly in content from force to force.

So that is the number one fundamental problem - what is being counted, how is it counted and is it the same through out the country?

Firstly how did I create the map?

- I downloaded the neighbourhood data for all the forces (unfortunately the Sussex spreadsheet was empty) and created a force total of the five categories of crime and one category of anti-social behaviour for December 2010.

- I attempted to compensate for the different sizes of the forces by dividing the counts in the six categories by the latest published total police officer and staff numbers for each force. This has its problems (and benefits which I will argue elsewhere) but it is better in my opinion than dividing by resident population.

- I then wanted to cluster the data giving equal weight to each category (see my previous posts regarding clustering) so I standardized all the data by transforming them into Z scores. This shows the standard deviation either side of the mean creating positive and negative figures.

- I then decided the best probable number of clusters by using the Ward's Hierarchical method in SPSS 17 and choose 6. I then used the K means clustering method with the six clusters.

- The K means method allows a better understanding of what factors has influenced the clustering, allowing a classification of the clusters to be reliably undertaken. This classification is shown under the map above with a table showing the scores for the cluster centres.

- Now this is where I need help. I cannot find a shapefile for police forces in England and Wales. Edina has a shapefile for police force basic command units for England and a seperate one for Wales. I had to do a bit of editing to the .dbf file to show my classification at force level using ArcGIS.

But what are the data I am classifying and mapping here?

To be honest you I do not know, I could find no documentation to explain. Now I am assuming that the crimes are police recorded crime in Home Office Crime Types but it would not surprise me to find out that there have been problems in ensuring that every force is submitting exactly the same types of crime. The chances of that being uniformly the same is a lot higher than the Anti-Social Behaviour figures, which I am assuming are from the police incident recording database and would not surprise me if they differ significantly in content from force to force.

So that is the number one fundamental problem - what is being counted, how is it counted and is it the same through out the country?

Wednesday, 2 February 2011

New crime mapping site - impressive but with fundamental problems

The new UK Internet Crime Mapping site was launched on Monday. It has received so many hits, reportedly 18 million an hour in the first few hours that I have had to wait until this morning before I managed to connect to the site.

I am torn between being impressed and dismayed, between thinking this is a leap in the right direction to thinking that the people who have designed this have not a clue what they are doing; between applauding the liberating of police data to castigating the fact that data without context and provenance cannot be treated as information.

First the positives.

I am torn between being impressed and dismayed, between thinking this is a leap in the right direction to thinking that the people who have designed this have not a clue what they are doing; between applauding the liberating of police data to castigating the fact that data without context and provenance cannot be treated as information.

First the positives.

- Innovation and development in public services require monetary investment and risks to be taken. It requires people in power to say `yes' to ideas rather than the safe 'no'. It is the way improvements and advances are made.

- Even though there are many problems with this site I think it should be seen leap in the right direction because it signals the acceptance of an underlying principle that the public have a right to know, in detail, what police are doing in their area through medium of police collected data.

- Connected with that is treating the public as grown up people who are capable of dealing with the harsh realities of life. This should lead to an understanding what the police know about the policing problems in the area thus enabling a more informed partnership between police and the public to tackle those problems.

- The visualisation of data is new, interesting and works smoothly at various levels of resolution. Technically it is interesting; it appears to work on a grid system of squares of I estimate 50 metres by 50 metres. The point shown at the highest resolution is on a road within that grid square closest to the centre (some grid squares seem to have more than one point at the highest resolution, I think this where two distinct post codes or street name can be identified - interesting algorithm). Everything georeferenced to a location within that grid square is shown at the point or points. The visualisation is of circles with the lowest resolution showing a circle with about a 5,000 metre diameter. As you zoom in and out the circles seamlessly change in size as the grid squares are subtracted or added. Different crimes types and antisocial behaviour counts are shown for the month of December 2010. The difficulties of counting across police borders appear to have been solved. There are links to Safer Neighbourhood Teams, with information about crime appeals, crime prevention, police Ward meetings and Neighbourhood Watch Schemes - all impressive.

I will leave the negatives which are fundamental and numerous until next time.

Monday, 24 January 2011

The British Crime Survey intial crime victimisation questions

I am going to try to explain something quite complex in this post but it is important to my research. It relates to the issue I discussed in my last post; the difference between the public's labelling of crime based the everyday use and common knowledge of the English language and the legal definition of criminal offences and how they are counted and categorised by the Home Office.

I have decided the best way to explain this is by reference to the methodology used in the British Crime Survey (BCS). The BCS is a survey of the general adult population of England and Wales that selects a sample of about 44,000 people a year to represent the total population about 44 million. The survey includes asking questions about whether the selected representative of the selected household has been a victim of crimes. Now because the interviewer can not assume that the person being interviewed has specialist knowledge about criminal offences within the England and Wales legal system there is a standard questionnaire that asks questions in everyday English.

A little bit of an aside the BCS in a masterpiece of covering just about every eventuality as one would expect from a piece of work that has been going almost 30 years and undergone numerous rigorous reviews of its methodology.

One of the first issues it covers is whether the person has moved in the relevant time, that is the last 12 months. This affects household victimisation, thus the slightly odd set of questions that are asked early on about crime types. These are listed in the table shown below.

The BCS dataset lists the numbers as options for variable `Crimtype' with the BCS data dictionary giving the names shown in the second column. I have examined the 25 sets of questions that produce answers regarding whether the household or individual has been subject to various events and if so how often. I have then used my specialist crime knowledge to explain the options. The way the questions are phrased allows burglaries to be identified. It is not possible though to differentiate between a theft person and a robbery as violence questions are at this stage dealt with separately to theft offences.

I have decided the best way to explain this is by reference to the methodology used in the British Crime Survey (BCS). The BCS is a survey of the general adult population of England and Wales that selects a sample of about 44,000 people a year to represent the total population about 44 million. The survey includes asking questions about whether the selected representative of the selected household has been a victim of crimes. Now because the interviewer can not assume that the person being interviewed has specialist knowledge about criminal offences within the England and Wales legal system there is a standard questionnaire that asks questions in everyday English.

A little bit of an aside the BCS in a masterpiece of covering just about every eventuality as one would expect from a piece of work that has been going almost 30 years and undergone numerous rigorous reviews of its methodology.

One of the first issues it covers is whether the person has moved in the relevant time, that is the last 12 months. This affects household victimisation, thus the slightly odd set of questions that are asked early on about crime types. These are listed in the table shown below.

The BCS dataset lists the numbers as options for variable `Crimtype' with the BCS data dictionary giving the names shown in the second column. I have examined the 25 sets of questions that produce answers regarding whether the household or individual has been subject to various events and if so how often. I have then used my specialist crime knowledge to explain the options. The way the questions are phrased allows burglaries to be identified. It is not possible though to differentiate between a theft person and a robbery as violence questions are at this stage dealt with separately to theft offences.

The table above should be read from left to right. The gaps signify where there is no comparable data. Even where there is comparable data there are caveats which I will cover in subsequent posts. What I want to point out is that the initial question (which seems to be to identify potential victims) with a little bit of recoding produces good results, ie consistent with published results. I do concede however that the data set I am dealing with only includes those cases that eventually were deemed to be offences.

Friday, 21 January 2011

Crime, soil, perception, labelling and mapping

There is a phrase up North that is "Call a spade a spade" or another one "Its what it says on the tin". The meaning of course is that the label given to something is 100% accurate and its all you need to know. The point I wish to make is that this is not the case with police recorded crime, which in the UK is the source data for crime maps. As I have discussed previously, for instance, the label `violent crime' is totally misleading. This I argue is at the heart of the public's mistrust in crime statistics. The requirements of police recorded crime to meet legal definitions, Home Office counting rules and groupings into Home Office types result in the label on the outside of the tin not representing what the public assumes to be on the inside of tin. It is not surprising therefore that the public's perception of various types of crime is different to what the police recorded crime statistics show. Then the there is the additional problem of unreported crime.

The question I have set myself is;

So that is the theory, what data is out there for me to use?

Let me give you an analogy off the top of my head.

When I travel round the countryside I notice ploughed fields, in different areas the soil is different colours varying from a rich dark chocolate through reds, yellows, greys, creams to almost white. That is my personal unsophisticated almost subconscious classification of soils, I am not a farmer, I am a city person, the countryside to me is about aesthetics and ambiance. Now to a farmer soil classifications are to do with what it consists of, its water retention and what he can and cannot grow on it; the soils are graded accordingly. I go into a map shop and decide that I want a map of different types of soil colours in the UK. The shop keeper tells me that there is not such a map but he can sell me one of grades of soils which is just as good because everyone knows the better the soil the darker in colour. I then test this assumption out only to find that it is not always the case. I want a map of what I can see not what requires specialist knowledge to understand. No doubt when grading the soil one of the early scientific observations would have been the colour, so it would be quite easy to produce a map of UK soil colours if the original soil grading data could be accessed.

So the data I am going to use is not the data for specialist that has been accurately sorted and classified - police recorded crime but the aspect of the data that the public observe and label in everyday language. I am going to the early stages of the data collection process.

I will make this clearer in my next post.

Reference

Jackson, J. and Bradford, B. (2010). 'What is Trust and Confidence in the Police?', Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 4,3, 241-248

|

| Link |

I have been a little bit silent on my research for a few weeks for various reasons but I think it is the right time to try to explain what I am up to.................

There is a phrase up North that is "Call a spade a spade" or another one "Its what it says on the tin". The meaning of course is that the label given to something is 100% accurate and its all you need to know. The point I wish to make is that this is not the case with police recorded crime, which in the UK is the source data for crime maps. As I have discussed previously, for instance, the label `violent crime' is totally misleading. This I argue is at the heart of the public's mistrust in crime statistics. The requirements of police recorded crime to meet legal definitions, Home Office counting rules and groupings into Home Office types result in the label on the outside of the tin not representing what the public assumes to be on the inside of tin. It is not surprising therefore that the public's perception of various types of crime is different to what the police recorded crime statistics show. Then the there is the additional problem of unreported crime.

The question I have set myself is;

Is it possible to produce valid crime data that more closely matches people's perception of crime for mapping purposes?This is a sentence I have used when trying to explain the the importance of this ambition;

We agree with others (see Jackson and Bradford 2010) that trust is aligned with effective community engagement based on a shared understanding of problems to be addressed, which in turn leads to increased confidence in the police and the criminal justice system.The problem of producing maps with data that the public do not trust is that it is likely to result in the public thinking that the police do not understand the crime problem. If the public do not think the police understand the crime problem it is logical for them to think that they are not tackling it properly, this inevitably leads to the public losing confidence in the police.

So that is the theory, what data is out there for me to use?

Let me give you an analogy off the top of my head.

When I travel round the countryside I notice ploughed fields, in different areas the soil is different colours varying from a rich dark chocolate through reds, yellows, greys, creams to almost white. That is my personal unsophisticated almost subconscious classification of soils, I am not a farmer, I am a city person, the countryside to me is about aesthetics and ambiance. Now to a farmer soil classifications are to do with what it consists of, its water retention and what he can and cannot grow on it; the soils are graded accordingly. I go into a map shop and decide that I want a map of different types of soil colours in the UK. The shop keeper tells me that there is not such a map but he can sell me one of grades of soils which is just as good because everyone knows the better the soil the darker in colour. I then test this assumption out only to find that it is not always the case. I want a map of what I can see not what requires specialist knowledge to understand. No doubt when grading the soil one of the early scientific observations would have been the colour, so it would be quite easy to produce a map of UK soil colours if the original soil grading data could be accessed.

So the data I am going to use is not the data for specialist that has been accurately sorted and classified - police recorded crime but the aspect of the data that the public observe and label in everyday language. I am going to the early stages of the data collection process.

I will make this clearer in my next post.

Reference

Jackson, J. and Bradford, B. (2010). 'What is Trust and Confidence in the Police?', Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 4,3, 241-248

Thursday, 20 January 2011

Geography, Theresa May and Confidence

I have suddenly got more confidence in our Home Secretary Theresa May because I have discovered that she has a BA in Geography! A few other interesting facts that make me feel that I know her better if wikipedia is to be believed;

- her father was a Church of England Minister presumably of a high church persuasion given her first name and the fact that her early education was at a Convent School,

- her maiden name was Brasier, no doubt not pronounced as it reads, but not the easiest of names to live with,

- her constituency is Maidenhead which means that she is likely to be close enough to the Cameron's Oxfordshire cabal (who apparantly run the country) to be a part of the incrowd at the weekends.

Home Secretary Theresa May said that officials were now launching a review of how crime figures are collected and published in an attempt to improve public confidence.

The review would look at ways of cutting costs while making the figures more coherent.

"Any reductions in crime are welcome, however levels are still too high and we know these statistics only offer a partial picture about the level of crime," Mrs May said.

"More needs to be done to bring crime down and we need to take bold action to restore public trust in crime statistics.

"That is why I have asked the National Statistician to lead a review and why we are moving the publication of crime statistics out of the Home Office to an independent body.

"Improving public trust and confidence in crime statistics is crucial if we bare to improve transparency and empower local communities to hold authorities to account."The review should, and I think will, include crime maps for the public. I think I should, and I think I will try to get involved...............

Friday, 14 January 2011

The Joy of Statistics

I will be brief with this post because the link I think is only available in the UK.

I watched this program about statistics this evening on BBC 4 and even though I did not agree about everything it assumed about crime data I found it a very interesting and thought provoking. You can watch on on BBC iplayer following this link

Sunday, 9 January 2011

What is Crime? - notifiable offences?

I want to write about police recorded crime and notifiable offences. I wanted to give you a bit history to make it all a bit more interesting, otherwise it would have just been "police recorded crime is confined to notifiable offences. They are called notifiable offences because the Home Office requires all Home Office police forces to notify it of the numbers of these crimes that occur each year in their territorial jurisdiction based on Home Office counting rules". The current ones can be found here, which also includes a link to a list of notifiable offences.

You would think the reason why no one has apparently written a paper outlining how the system came about is because it is deadly boring and not worth the effort. I actually think it is a quite an interesting story if I have got the right end of the stick - my sole source is Hansard, the official record of parliamentary proceedings and therefore quite a good source; it is now helpfully on line from 1803 onward.

The first mention of crime in online Hansard is in 1824 in a debate about magistrates and the increased level of committals, convictions and executions. This was of course before the first police force was introduced - the Metropolitan Police in London in 1829. It is apparent from the debate that the moral health of the country was measured by these Crown Court statistics which had been collected for at least 15 years before the debate. In fact in 1828 it was these same source of statistics that was used by the Home Secretary Robert Peel to show that committals had increase by almost a third in the previous seven years to justify the introduction of the Metropolitan Police Service.

Possibly the most scathing attack on government statistics ever was made by Lord Brougham on 3rd of March 1856 (in the House of Lords) when he showed that the Judicial Statistics that had provided evidence for Government policies for at least the previous 40 years were worse than useless. Even more embarassing was the fact that the equivalent French statistics based on Guerry's work were almost perfect in comparison, at least according to Lord Brougham. The speech included the following;

Exactly a week later on 10th March 1856 the Police (Counties and Boroughs) Bill was debated in the House of Commons. This became the Counties and Boroughs Police Act 1856 that made it compulsory for any County or Borough that did not already have a police force to introduce one. It also created what is now Her Majesties' Inspectorate of Constabularies to report regularly to the Home Secretary regarding the efficiency of each police force (see here). It is known that the first police recorded crime statistics were collected for the year 1856 so there seems to have been some co-ordination behind the scenes for the Home Office to draw up a list of notifiable offences.

You would think the reason why no one has apparently written a paper outlining how the system came about is because it is deadly boring and not worth the effort. I actually think it is a quite an interesting story if I have got the right end of the stick - my sole source is Hansard, the official record of parliamentary proceedings and therefore quite a good source; it is now helpfully on line from 1803 onward.

The first mention of crime in online Hansard is in 1824 in a debate about magistrates and the increased level of committals, convictions and executions. This was of course before the first police force was introduced - the Metropolitan Police in London in 1829. It is apparent from the debate that the moral health of the country was measured by these Crown Court statistics which had been collected for at least 15 years before the debate. In fact in 1828 it was these same source of statistics that was used by the Home Secretary Robert Peel to show that committals had increase by almost a third in the previous seven years to justify the introduction of the Metropolitan Police Service.

Possibly the most scathing attack on government statistics ever was made by Lord Brougham on 3rd of March 1856 (in the House of Lords) when he showed that the Judicial Statistics that had provided evidence for Government policies for at least the previous 40 years were worse than useless. Even more embarassing was the fact that the equivalent French statistics based on Guerry's work were almost perfect in comparison, at least according to Lord Brougham. The speech included the following;

Hitherto I have spoken of offences and offenders as recorded in the proceedings of courts, whether of trial or of police; but it is of the greatest importance to ascertain as far as possible the number of crimes which never reach any court: nothing can be more essential to the formation of an estimate touching the state of crimes in the community, and the action of the law in detecting and in preventing them.His long speech came to an end with a very long list of judicial statistics that should be collected in the future including crimes that do not reach the courts - police recorded crime. In reply the Lord Chancellor said that Lord Brougham suggestions would be looked at seriously.

Exactly a week later on 10th March 1856 the Police (Counties and Boroughs) Bill was debated in the House of Commons. This became the Counties and Boroughs Police Act 1856 that made it compulsory for any County or Borough that did not already have a police force to introduce one. It also created what is now Her Majesties' Inspectorate of Constabularies to report regularly to the Home Secretary regarding the efficiency of each police force (see here). It is known that the first police recorded crime statistics were collected for the year 1856 so there seems to have been some co-ordination behind the scenes for the Home Office to draw up a list of notifiable offences.

Monday, 3 January 2011

What is crime? - recordable offences?

I know I am feeling better, because I have an urge to write something that probably is no interest to anyone but myself. I went on a short trip to Thailand and Vietnam just before Christmas and managed to get home just before the snowfall landed on Heathrow. Unfortunately I managed to eat something that upset my stomach quite dramatically and after that I picked up a virus from IBM. Not a computer virus - a man flu virus via my son in law who works for IBM. That slowed me down a bit but unlike the previous bug it did not stop me eating so I did enjoy Christmas, thanks for asking, but I have not felt up to doing the work I was planning. Thus the absence of posts.

Now what has got my mental juices flowing again? Its the problem of defining "crime".

The first thing to say that I am approaching this from my knowledge of the English and Wales legal system. There are many other legal systems out there...................

In our legal system there is a fundamental principle that is even more basic than "innocent till proven guilty" which is often misquoted and misunderstood -you are guilty the second you commit an offence but for the purposes of the criminal justice system you are regarded as innocent until due legal process proves you guilty beyond reasonable doubt. The principle I am referring to is that a crime has to be defined (usually) by legislation. The criminal law assumes everything is legal that is not specifically enshrine in Common Law, defined as a criminal offence by Act of Parliament, or arguably a body permitted by Act of Parliament to create offences - thus local bylaws. Criminal Law has its own courts, rules and sanctions.

Travelling in parallel with Criminal Law but very much on its own tracks is Civil Law. Civil Law has all sorts of weird and wonderful things but it does not have offences and crimes. It can be said that criminal law deals with absolutes that if put into questions should have a yes or no answers. Civil Law on the other hand deals with gradations whose answers are more fuzzy - maybes and depends are better answers. And of course the burden of proof in civil cases is on the balance of probabilities that reflects these differences.

But I digress. What I am trying to show is that with a legal system such as the English and Wales one the broadest legal definition of crime is an offence under criminal law. This of course includes parking offences, speeding fines, littering, drunkeness in a public place and other offences that we generally regard as being committed by normal members of the public, not criminals.

To have a criminal record you have to have been convicted of a recordable offence. Once you have been convicted of a recordable offence you are allocated a unique number (and letter) which in the days when the record was a paper file in the Criminal Records Office at new Scotland Yard was known as a CRO number. That's why when you get charged with a recordable offence you have your fingerprints and photograph taken. Now in a more modern world the record is no longer paper it is computerised on the Police National Computer (PNC) and you are allocated with a PNCID instead of a CRO. There are of course still people with both. And nowadays DNA is also taken as an identification. Details of what are recordable offences are here. Recordable offences are basically offences that have a term of imprisonment as a sanction plus a number of specified offences.

Now this is the confusing bit; the official crime statistics - police recorded crime - is a system that is quite separate from the recordable offences discussed above and it is based on notifiable offences. But that is for the next post.

Now what has got my mental juices flowing again? Its the problem of defining "crime".

The first thing to say that I am approaching this from my knowledge of the English and Wales legal system. There are many other legal systems out there...................

In our legal system there is a fundamental principle that is even more basic than "innocent till proven guilty" which is often misquoted and misunderstood -you are guilty the second you commit an offence but for the purposes of the criminal justice system you are regarded as innocent until due legal process proves you guilty beyond reasonable doubt. The principle I am referring to is that a crime has to be defined (usually) by legislation. The criminal law assumes everything is legal that is not specifically enshrine in Common Law, defined as a criminal offence by Act of Parliament, or arguably a body permitted by Act of Parliament to create offences - thus local bylaws. Criminal Law has its own courts, rules and sanctions.

Travelling in parallel with Criminal Law but very much on its own tracks is Civil Law. Civil Law has all sorts of weird and wonderful things but it does not have offences and crimes. It can be said that criminal law deals with absolutes that if put into questions should have a yes or no answers. Civil Law on the other hand deals with gradations whose answers are more fuzzy - maybes and depends are better answers. And of course the burden of proof in civil cases is on the balance of probabilities that reflects these differences.

But I digress. What I am trying to show is that with a legal system such as the English and Wales one the broadest legal definition of crime is an offence under criminal law. This of course includes parking offences, speeding fines, littering, drunkeness in a public place and other offences that we generally regard as being committed by normal members of the public, not criminals.

To have a criminal record you have to have been convicted of a recordable offence. Once you have been convicted of a recordable offence you are allocated a unique number (and letter) which in the days when the record was a paper file in the Criminal Records Office at new Scotland Yard was known as a CRO number. That's why when you get charged with a recordable offence you have your fingerprints and photograph taken. Now in a more modern world the record is no longer paper it is computerised on the Police National Computer (PNC) and you are allocated with a PNCID instead of a CRO. There are of course still people with both. And nowadays DNA is also taken as an identification. Details of what are recordable offences are here. Recordable offences are basically offences that have a term of imprisonment as a sanction plus a number of specified offences.

Now this is the confusing bit; the official crime statistics - police recorded crime - is a system that is quite separate from the recordable offences discussed above and it is based on notifiable offences. But that is for the next post.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)